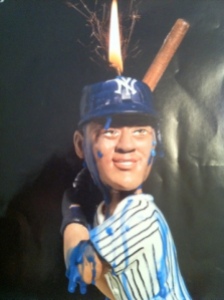

The cover of the June 26th issue of the New York Times Magazine featured a candle that looked just like Yankees’ shortstop Derek Jeter, holding a bat as if waiting for the next pitch from, perhaps, a candle that looked like Tim Wakefield. The Jeter candle was lit, and navy blue rivulets of melting wax ran from the hat down the pin-striped uniform into the butter cream frosting.

The cover of the June 26th issue of the New York Times Magazine featured a candle that looked just like Yankees’ shortstop Derek Jeter, holding a bat as if waiting for the next pitch from, perhaps, a candle that looked like Tim Wakefield. The Jeter candle was lit, and navy blue rivulets of melting wax ran from the hat down the pin-striped uniform into the butter cream frosting.

The story, titled “For Derek Jeter, on His 37th Birthday,” was about how the Yankees’ captain, who turned 37 on June 26, has been in a type of hitting slump known as “aging.” The fancy scientific reason the beloved Yankees’ captain has not been as productive behind the bat, whether made of ash or candle wax, is because of age-related degradation in his fast-twitch muscles. Jeter now, apparently, requires a full half-second to decide whether to swing at a 90 m.p.h. pitch, rather than the mere quarter-second required in his 20s and early 30s.

I wonder how my fast-twitch muscles are faring these days. I notice that I am not squashing bugs as quickly as I used to. When driving, I do not swerve around roadkill as deftly as I once did. And it now takes me a full two seconds to change the channel whenever that annoying commercial for Progressive Insurance with Flo comes on, whereas I used to change it almost instantaneously.

I remember when my parents turned 37. I noticed that my father was taking a few extra seconds to pull the car over to the side of the road to yell at me for tormenting my brother with the business end of a seat belt. And when I went to the supermarket with my mother, I could swap the Cheerios with Fruity Pebbles before she could turn her head. I felt bad taking advantage of my parents’ aging, but Mariano Rivera would have done the same thing.

All around me I see evidence of age-related degradation of fast-twitch muscles. Insurance adjusters taking a few minutes longer to reject my claim. Cops taking a few extra seconds to flip on their lights when I go flying by them at roughly the same speed as a major league pitch. Even the worker at the deli I frequent—he couldn’t have been a day over 32—did not react quickly enough to my direction of no onions when making my sandwich, leaving me to pick them out myself.

When I was younger I was always very fast at tying my shoes. If I was inside watching television and heard, say, the ice cream man coming down the block, I would have my sneakers on and tied inside of 15 seconds, faster than it took my mother to say that I wasn’t getting any ice cream until I scraped the Silly Putty off the ceiling.

Just the other day I was lying in bed and heard the sound of the garbage truck coming down the block, and I realized, with a panic, that I’d forgotten to put out the paper garbage. Naturally terrified at the prospect of going another two weeks with a mountain of Penny Savers and empty boxes of Count Chocula overflowing the blue bin in my garage, I leaped out of bed and ran downstairs. I didn’t care if my hair was sticking out in several different directions, and I didn’t care if my neighbors saw me in my Spider Man pajama pants. But I didn’t dare go barefoot; that’s a good way to get a splinter.

I tied my sneakers as fast as I could, but something was missing. Like the unnamed scout observed about Derek Jeter, my hands were slower, and my feet were slower. I now know that a hundredth of a second separates not only a line drive to center field and foul tip into the stands, but also an empty blue recycling bin and a full one. As I dove in vain towards the departing truck, I heard the sanitation worker say, “Close only counts in horseshoes and hand grenades.”

So to Derek Jeter, I say: Happy birthday, hope you get your 3,000th hit, and invest in some Velcro cleats.

Have you noticed any degradation in your fast-twitch muscles or in the fast-twitch muscles of the people around you?