My first blog was created in the fall of 2008. America was in the midst of a Presidential election, and debate was fierce. While showering I came up with a few ideas on how to solve the financial crisis and the exploding cost of healthcare. I published a few posts sharing my views, and dreamed of appearing on television news programs with the words “Freelance Public Policy Expert” floating under my talking head.

When I clicked on “publish” it was as if a jolt of electricity had gone through my body. I imagined that my post would instantly show up on everyone’s screen like that persistent prompt to download the latest version of Abode Flash Player. Now our leaders would know what to do. But none of my posts got any comments, or any views, and every Sunday morning it was the same group of politicians, journalists, and well-established experts on the Meet the Press instead of me.

My second blog was daily vignettes and flash fiction. I wrote about annoying cell phone conversations and chronic snifflers and people who carried large pieces of luggage onto commuter trains during rush hour. I wrote a story about a device called the Descriptionizer Functioner, even though I did not know what it did, and another story about a man who can’t find parking in Manhattan until a UFO vaporizes a parked car right before his eyes. I had a great sense of accomplishment with each story, but still no one was reading. I figured it was because my characters had no depth.

At no point did it occur to me to tell anyone what I was doing.

Then it was early summer and getting hot, and I was taking another stab at the collected works of William Shakespeare. I try this every summer. I was supposed to have read Hamlet in the 12th grade, but I was busy slacking off at the time. Better late than never, I decided a great way to learn the play was to write a humorous parody of it and post my work to a blog. I wrote it up, and then I moved onto Macbeth, which I liked because it had lots of rhyming and is very short. At last I had found my blog concept. I would write a blog making a parody of each Shakespeare play. But I hit the wall at King Lear. At first I thought my problem was that I did not understand the text. Then I saw the movie – the recent one with Sir Ian McKellen – and realized that the play is just really disturbing.

Then I was blogging journal entries about my daily life. I wrote about coffee and cat food. I wrote about looking for a copy of a video I made when I was running for class president. I wrote about my office mate who seemed to do nothing but sip soda and chew gum. And then I got bored and stopped.

The blogging thing just didn’t seem to be working. I was glad I hadn’t told anyone about it.

Then I was home for Columbus Day and considered loitering in front of a convenience store to pass the time. Suddenly I remembered a cartoon show called Beavis and Butthead that had aired on MTV in 1993. I remembered how fond I had been of that show, and how the base and tasteless humor had spoken to me at a time when I was fairly base and tasteless myself. And I saw how I could write a post about it. The short post occurred to me all at once, and after I wrote it I thought of other things that had changed in the last few decades.

The topics seemed inexhaustible. I blogged for a few weeks, and mustered up the courage to tell my mother about it. I got decent feedback from my mother, and then I told my wife. My wife gave me decent feedback, too, especially after I shoveled the driveway and took out the garbage. Then I told my dearest, closest friends. Then I told my Facebook friends. And I saw that the feedback was good. I kept blogging for them, and then one day I was Freshly Pressed and had the greatest experience I know as a writer – being read by thousands of strangers.

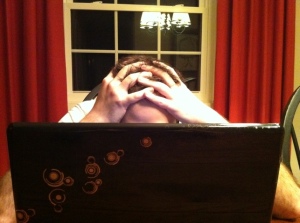

And now I can’t stop blogging. I think about it when I’m supposed to be paying attention to people who are talking to me. At least I have an inexhaustible concept for posts. “Remember when…” There’s no end to that! No way would I ever break with such a concept.

So what’s your story? How did you start blogging?